When discussing China’s railways, it’s impossible to overlook the impressive records and superlatives. The country boasts the largest high-speed rail network in the world, built at an unprecedented pace and with colossal investments, all while maintaining unmatched low costs. How did China manage to develop such infrastructure within just a few decades?

Strategic Thinking as the Engine of Progress

China is known for its long-term planning and targeted strategies. From industry to digitalization and political issues, the country follows a clear course. This is also true for railway infrastructure: In the late 1990s, the Chinese government decided to connect the country with a network of high-speed trains to accommodate the urbanization that was growing alongside the development of the socialist market economy. It was a bold move that would soon yield impressive results.

Shortly after, China began constructing high-speed lines at a breakneck pace. In 2003, it was estimated that 8,000 kilometers would be built within 30 years. That same year saw the launch of the first dedicated high-speed line, the Passenger Dedicated Line (PDL) from Shenyang to Qinhuangdao, as well as the Maglev transfer to Shanghai Airport.

Just ten years later, in 2013, the network had reached over 10,000 kilometers – more than all of Europe’s high-speed rail lines combined.

A Network That Circles the Globe

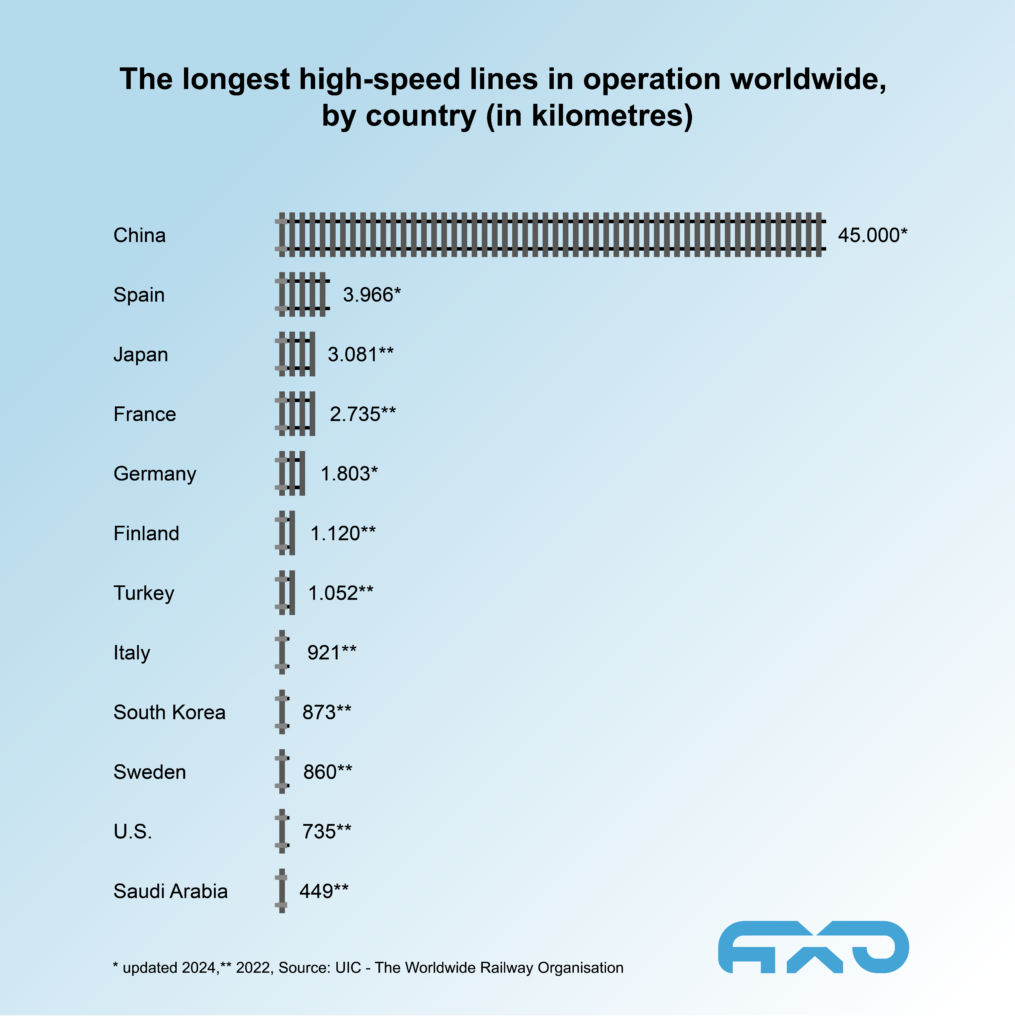

Today, China’s high-speed rail network spans over 45,000 kilometers. That’s enough to encircle the globe!

For example, in April 2024, the Chizhou – Huangshan line was put into operation. More lines are scheduled to be completed throughout the year, with others under construction or in planning stages. Almost all cities with more than 200,000 residents are now connected to the rail network, with 80 percent also linked to the high-speed network.

This remarkable growth is attributed to massive investments. In just the first five months of 2024, over 228 billion yuan was injected into railway expansion, representing a 10.8% increase compared to the previous year. But how is it possible to implement such projects in such a short time and at relatively low costs?

Efficiency through Planning and Standardization

In addition to state investments, the combination of government planning and economic execution is the key to success. While many Western countries take years or even decades to construct high-speed lines, China often accomplishes this in a fraction of the time and at significantly lower costs—reportedly at no more than two-thirds of the expenses incurred by high-speed rail projects elsewhere.

The reasons for this lie in low labor costs in China, as well as the large-scale standardization of construction elements and the development of cross-project manufacturing capacities for equipment. This enables efficient and cost-effective production, distributing costs across many projects.

Moreover, the rapid construction performance can undoubtedly be attributed to the Chinese system—what often causes delays in other countries, such as lengthy approval processes with public hearings, legal disputes across multiple jurisdictions, or even blockades by environmentalists, simply does not occur in the People’s Republic.

Rail in China: Train Beats Plane

The efficiency of the Chinese high-speed network is particularly evident when compared to air travel. On routes such as Beijing–Shanghai, trains have long surpassed planes. Although train journeys take slightly longer than flights, the time savings from quick access to train stations and frequent connections offset this difference. Furthermore, tickets are cheaper, and trains are more punctual. It’s no wonder that many domestic flight routes now face competition from rail.

According to the study “Impact of High-Speed Rail on China’s Big Three Airlines,” by 2025, up to 80% of domestic flights in China will have to compete with high-speed trains. Currently, rail lines are experiencing annual passenger increases of around 30%.

Infrastructure Highlights

High-speed lines typically skirt city centers. New long-distance stations like Beijing South and Zhengzhou East have been built, with connections to the subway, linking to city centers and airports.

Impressive engineering structures have been created for many segments of the routes. For instance, the Beijing–Shanghai high-speed line crosses the Danyang–Kunshan Bridge, which, at nearly 165 kilometers long, is the longest bridge in the world, spanning not only the Yangtze River but also more than 150 wide river arms, rice fields, lakes, and villages. Another record was set here: the bridge was completed in just four years at a cost of $8.5 billion.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationEqually impressive is the Taihang Mountain Tunnel, the longest tunnel on a high-speed line at 27.84 kilometers. It allows trains to traverse from Shijiazhuang to Taiyuan at speeds of up to 350 km/h, reducing the journey time from six hours to just one hour.

To ensure train operation, the CTCS system is employed, which is technically closely related to the ECTS system.

Innovations: China Keeps Advancing

However, China is not resting on its laurels. New technological breakthroughs continue to be developed. Here are two innovations:

Lightweight and Modern: Carbon Star Rapid Transit

In July 2024, the world’s lightest train was introduced: the Carbon Star Rapid Transit, also known as Cetrovo 1.0, is made almost entirely from carbon-fiber-reinforced plastic (CFRP). Even the frame of the bogie, which carries the axles and wheels, is made from this material, which is said to be five times harder than steel but weighs only a fraction of it.

Overall, the Cetrovo 1.0 weighs 11 percent less than a conventional train and consumes 75 percent less energy, resulting in annual savings of around 130 tons of carbon dioxide emissions.

The Carbon Star Express is set to launch on the first subway line in Qingdao in 2024. It is designed to reach a maximum speed of 140 km/h and operates fully automatically and without a driver.

Hyperloop Faster than a Plane

In addition to the lightest train, there will also be the fastest: By 2035, China aims to build its first commercial Hyperloop line, connecting Shanghai and Hangzhou over a distance of 175 kilometers. Initial test runs of the T-Flight in February and July 2024 achieved a top speed of 623 km/h over just two kilometers. Using magnetic levitation technology and vacuum tubes, this transforms high speed into UHS: Ultra-High Speed.

The second phase of testing is expected to cover 60 kilometers and accelerate to 1,000 km/h. The state-owned Chinese defense conglomerate Casic, responsible for construction, even talks about possible speeds of up to 4,000 km/h. For comparison, passenger airplanes typically have cruising speeds between 700 and 900 km/h, with rare instances reaching 1,100 km/h. It remains to be seen whether this extremely expensive and energy-intensive technology will gain traction amid China’s current economic challenges.

With the T-Flight, China breaks its own record: The Shanghai Maglev Train (SMT) was previously the fastest train in the world.

Criticism of Technology Transfer and Competition

Despite these impressive advances, there are also critical voices regarding how China has acquired technical knowledge. Through political directives and savvy negotiations, Western companies have been brought into the country over the past decades. They were required to cooperate with Chinese partners, who hold the majority shares in joint ventures, making technology transfer a legal requirement. Technology transfer and production in China have been mandated by law.

An example includes the high-speed trains that emerged from tenders in 2004 and 2005. The CRH1 incorporates Bombardier technology (Regina and Zefiro), the CRH2 comes from the Shinkansen family (E2), the CRH3 is based on Siemens Mobility (Velaro), and the CRH5 on Alstom (Pendolino). There is no CRH4, as the number is considered unlucky. Most models have been produced under license in China and serve as the basis for modern, entirely Chinese-made trains.

As a result, China has increasingly managed to become independent from Western technology in recent years. With its own patents and standards, the country is now competing on the global market against established manufacturers, but under unbeatable conditions:

One of China’s major advantages is its low-cost labor. This allows the country to offer its developments at very low prices in other countries. The term “price dumping” is often mentioned within the industry.

Conclusion

China’s success in the railway sector is impressive and symbolizes the rapid economic development and technological innovation of the country. No other nation has managed to establish such a comprehensive high-speed network in such a short time. The efficiency behind this mammoth project is commendable, as are the technological innovations that China continuously advances.

It will be exciting to observe how this development unfolds in the coming years—and which superlatives the country will achieve next. While China has undoubtedly become a global player in the railway industry, it remains to be seen whether it can also tackle the challenges that come with its ambitious pace in the long term.